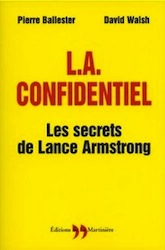

David Walsh, author of the infamous LA Confidentiel and one of the most notable contemporary voices against doping, was quoted in Cyclingnews a few days ago, commenting on the high-profile positives of the past month. “You’ve now got Contador and Mosquera both in trouble” sighed the Irishman, “and you have to think that this sport is going nowhere.”

David Walsh, author of the infamous LA Confidentiel and one of the most notable contemporary voices against doping, was quoted in Cyclingnews a few days ago, commenting on the high-profile positives of the past month. “You’ve now got Contador and Mosquera both in trouble” sighed the Irishman, “and you have to think that this sport is going nowhere.”

While I respect the man’s opinion, I think his statement couldn’t be further from the truth. Even as I type this, the allegations made in his book are flushing out the foundation of a federal case against Lance Armstrong and the former US Postal Service Team. A deposition prompted by Walsh’s investigation has already caught the seven-time Tour winner in an obvious contradiction, and for those eager to see the Texan’s head on a platter, the best may be yet to come.

But cycling’s steps toward a cleaner sport over the past few years go well beyond exposing les secrets de Lance Armstrong. Though the progress has been slow, and it’s easy to lose sight of the big picture with each new positive test, the long-term trend has been turning solidly and inexorably against the dopers.

Consider 2004, the year in which LA Confidentiel made its debut. That fall, Tyler Hamilton recorded the first positive sample under new testing for homologous blood transfusions (the re-injection of someone else’s blood). Aside from proving the efficacy of the new test, the Hamilton case also revealed to exactly what extent the anti-doping authorities were able to monitor the blood samples they took; thanks to Hamilton’s rigorous legal battle, the scientific validity of this testing was thoroughly established.

This detailed monitoring—which would eventually become the UCI biological passport program—sent the message that successfully-executed doping would now be a full-time job, requiring careful dosing, refrigeration, planning, and support from medical professionals: none of which come cheaply or easily. Even the deep-pocketed Hamilton, whose doping program was extensive and well-planned, still hadn’t been able to dodge the vampires or beat the rap.

2004 was also the year of Jesus Manzano’s revelations about the pervasiveness of doping within the cycling world. Manzano, a middling Spanish rider, opened up to the Spanish press with a flood of allegations, which were categorically denied and dismissed by cycling’s establishment. But the maligned Spaniard’s work with authorities bore fruit in a 2006 raid on the offices of Dr. Eufemiano Fuentes.

2004 was also the year of Jesus Manzano’s revelations about the pervasiveness of doping within the cycling world. Manzano, a middling Spanish rider, opened up to the Spanish press with a flood of allegations, which were categorically denied and dismissed by cycling’s establishment. But the maligned Spaniard’s work with authorities bore fruit in a 2006 raid on the offices of Dr. Eufemiano Fuentes.

Despite massive interference from the Spanish government, the Opercion Puerto case lead directly to the accusation and punishment of countless riders, including three serious TdF contenders: Ivan Basso, Jan Ullrich and Alejandro Valverde. While the case was never as far reaching as it should have been, and progressed with interminable slowness, the actual sanction of top-tier TdF finishers was a first since the cycling “owned up” to the extent of oxygen vector drug abuse in 1998.

Between 1998 and 2005, there were no major changes in the UCI rules—EPO and blood doping were just as illegal as they are today. But before the Hamilton positive and Puerto raid, efficacy of testing and enforcement had been decidedly lacking. Both homologous doping and EPO lacked a good tests for years, and early positives were met with skepticism and short suspensions. At some points, authorities may even have turned a blind eye to higher-profile positives.

Consider the Tours since the Puerto raid, and I think you’ll see a definite change. In ’06, Landis was caught after a miraculous, ride-away-from-everyone Tour win, just days after the Tour ended. In ’07, Vinokourov was caught re-injecting someone else’s blood and booted mid-race. Later that same year, Michael Rasmussen was voluntarily pulled by his team while wearing the Yellow Jersey, after his violations of the UCI’s whereabouts policy were revealed.

In 2008, a few riders, riding high on the general classification and throwing back stage wins like energy gels thinking they’d discovered an undetectable new drug, were caught and very visibly ejected, along with a handful of other names sanctioned after the fact. And now, in 2010, we have Alberto Contador caught shortly after the Tour with nearly-undetectable levels of a drug, and chemical substances that, while not sanctionable yet, strongly suggest re-injected blood.

If those previous two paragraphs don’t represent a remarkable increase in testing effectiveness, I don’t know what does. And it’s really just the continuation of a longer-term trend. Consider the Tour podiums from 1999-2005. While it is glaring that the most successful rider of that era remains at least technically innocent, it’s difficult to find another Head of State from the period with whom justice has not caught up. When compared with the soft or non-existant sanctions placed on riders in the Festina era, even those slow-moving cases mark a dramatic improvement.

The initial reaction when inundated by news of positive tests—as Walsh and Ettore Torri have recently voiced—is to throw up your hands and say that everyone’s on drugs and that nothing is improving. But natural though that instinct may be, it’s also highly irrational.

The initial reaction when inundated by news of positive tests—as Walsh and Ettore Torri have recently voiced—is to throw up your hands and say that everyone’s on drugs and that nothing is improving. But natural though that instinct may be, it’s also highly irrational.

Positive tests mean riders are getting caught. While the confessions of some riders make test evasion seem trivially easy, their own positives contradict that suggestion. There’s no argument to be made that an effective doping program isn’t a massive undertaking today, especially compared with the casual EPO needlesticks of a decade ago.

While the UCI may at times seem to be doing everything in its power to erode public faith in the sport, the fact remains that cycling’s progress in rooting out dopers has been commendable, and the improvements are continuing. Bernhard Kohl’s well-worn quip that you cannot win the Tour without doping may indeed still be true, but the cost, complexity, and risks involved in dosing up are exponentially higher than just a few years ago—as his own downfall reflects. If testing continues to improve, in the very near future, it may no longer be worth the reward.

The dream of a sport—any sport—with no doping is an attractive fantasy, but a fantasy nonetheless. As long as there is competition, people will cheat to gain an extra edge, and those hunting the cheats will always be playing catch-up. The best a rational fan can hope is that those running the sport make cheating as unattractive a proposition as possible, through consistent, effective testing, and firm, swift sanctions.

And in that regard, I think you’d be hard pressed to find a sport going in a better direction than professional cycling.

I agree with your opinions here. It is notable that some of the biggest names in cycling are facing serious recourse for what they may have done. The cycling community owes the various sanctioning bodies some recognition for the progressiveness in doping control over the last decade.

That is not to say that we should maintain the status quo and stop progress…

The conclusion of this entry is that doping “may no longer be worth the reward.”I suppose it might not. Then again it might still be (See last winners of the Tour since 1992). Some argument.

What hasn’t changed is that commentators are always ready to believe whatever crazy story a famous doper comes up with — or at least for the first few years, or until the guy himself admits it. Didn’t you post that you were “impressed” with Contador’s laughable presentation? The conference where he said that he ate “contaminated” meat?! That’s almost as silly as Landis’ “I drank Jack Daniels” excuse.

Another constant in cycling is the willingness to forget about the little guy, namely (for example) that nameless chinese dude on Radioshack who got busted for clenbuterol a few months ago and summarily fired without further ado. He was banned by the UCI for two years what 30 seconds after his B sample came back positive? Without words of support from Johan the B, without an initial sympathetic post on cyclocosm.com or anywhere else for that matter…

What else is knew in the world of cycling besides subservience to the current superstar and scorn for the whistle blower, be it Walsh, Kohl or Landis?

Not much. Lance is still unpunished and as of right now Contador has received preferential treatment.

I suppose the only difference is that the public is more aware of the prevalence of cheating in cycling and more conscious of the hypocrisy of the specialized press. And if you think that means things are getting better or things are going to change, you are in denial. People said this after the Festina scandal compared to which, the current shitstorm is a tempest in a tea-pot (they almost stopped the Tour mid-way, for Christ’ sakes). Nothing changed after the Festina affair besides an intial outrage and predictions thing would change, but they did not. If anything it got worse!

Walsh is right, this sport is going nowhere.

Although it’s not perfect, cycling is definitely doing more to curb doping than most other sports.

I turned on the radio this morning and heard that the winner of the 100m sprint at the Commonwealth Games had tested positive for a banned stimulant. The reporter noted that four Jamaican athletes had tested positive for stimulants earlier this year and had been given a ban of three months last month. THREE MONTHS! That length of suspension was being given to cyclists who tested positive way back in the 90’s. Given that, it seems that anti-doping efforts in cycling are literally decades ahead of other sports.

Positive tests that are public knowledge means some riders are being caught. The UCI does what it pleases with WADA findings.

Your writing is clearly from the heart. Good on you for putting it out there.

However, the longer you pay attention to the sport, (especially stage racing) the sooner you will get to Walsh’s perspective.

@Oliver: I’d say the conclusion of this piece is that, although you can’t ever stop people from doping, cycling’s been getting progressively better at it since 1998.

If you believe every Tour winner since ’92 was on drugs (and I wouldn’t bet against it), how can you look the sanctions served by/facing Tour winners from ’10, ’09, ’07 (twice) and ’06 and think that progress isn’t being made? Is your contention that it was better when everyone got off scot-free?

Being “impressed” with Contador’s presentation was a commentary on his media management, not the substance of his defense. Keep in mind, this is a guy who had to turn to YouTube to produce a palatable statement on Chaingate, and couldn’t manage to look in the same direction for more than 2 seconds during his TV interviews on Versus.

As for trend to scorn the whistle blower, it certainly exists—but I think I’ve done a pretty fair job of coming out against it. I will readily admit to disliking the sweeping scope that Kohl uses in his declarations for the same reason Mike Creed does.

@dity_juheesus!: It’s interesting that you said that bit about being “from the heart.” As I said in the post, I think Walsh’s perspective (which I do understand) is far more emotional than my own. Objectively speaking, how is it a bad thing when dopers get caught?

I agree with your statements copmletely Cosmo. I would like to know who you think is riding clean and getting strong results in grand tours and/or across the whole season?

@cyclosm: I think we would (should?) agree that every major Tour contender has been doping in the last few years (with the notable possible exception of 2008, when the UCI was not involved in the testing directly – coincidence?). But it’s more that that: domestiques are doing it too, and why do they get caught? Because they forget to drink a liter of water! In other words, it’s still relatively easy to get away with it.

The fact that this is out in the open is a good thing I don’t disagree, but let’s not get carried away: the thermometer works, great, ok. The problem lies with the fact that almost nothing is done about it once the big cheese get caught.

Georges Vecsey started an article the other day about cycling thusly: “Welcome back to cycling, where the dog often eats the homework.” That’s not the problem; the problem is that a lot of people are willing to believe it (Vecsey included!).

And to comment on the media presentation, on PR, when faced which such an obvious B.S. session on the part of Contador and his team of managers who have had weeks to prepare it courtesy of the bending of the rules by the UCI, what can I say? It’s like watching a bunch of cops beat up demonstrators & comment on how nice their uniforms look… So what?

So what’s different now? We all know what’s going on? I call motion to dismiss. It’s still going on the stars are not being punished in the way the domestiques are (Lance, Contador). The UCI is still dragging its feet kicking and screaming and covering up (note that the one possibly clean tour in recent years, 2008 was the one where the UCI was not directly involved in testing…). The media they are all along for the ride, pious homilies against doping included and positive spinning unworthy of even the worst political hack.

As to Kohl, what’s his crime? Saying that it is impossible to win the Tour without doping? I think that is a truism which every pro would privately agree with, starting way back when with Jacques Anquetil (who said it aloud, because he cold afford to). And you link to a guy whose response your agree with and consists of writing “failldozer” and “how the fuck would he [Kohl] know?” Not much to say here.

Just because we can no longer deny that Walsh was right all along, does not mean that things are going better. I think that the opinion of Ettore Torri (the Italian anti-doping prosecutor) who says doping is systematic in cycling helps bolster this analysis, not the opposite.

Once you detect the cancer, you don’t jump up for joy and congratulate yourself saying the testing works, you get to work fighting it. And right now we see and know that cycling is full of tumors: saying that knowing about it is positive is just cheap spin and does not help the sport in any way. Our sole concern should be about making the top cheats (Contador, Lance) and the UCI who have made all this possible, accountable.

Cosmo,

What I read was you have some optimism about Pro Cycling’s reputation as a juiced sport may be on the decline. You think WADA is doing good things (I agree) and that will lead to fewer PED positives.

I’m not condoning the PED use. A good day for the sport would be WADA enforcing the rider positives. Verbruggen and McQuaid won’t let that happen. Based on the way Pharmador’s positive was handled by the UCI, the UCI is still quite accommodating to PED use.

The consequence of accommodating PED use is the annual celebrity doping positives will continue. The UCI will do its best to put off the day of reckoning for the positive announcements while WADA will have positives queued up for months. That’s my prediction for the sport at the Continental Pro level unless the UCI is cleaned out.

For those that haven’t seen it, check out the Australian report on doping in the peloton done for the Geelong conference.

https://www.newcyclingpathway.com/

There is a change underway and it is primarily coming from the riders themselves and their attitudes. There will likely always be cheaters, but they may well become the exception if this trend continues.

The report talks a lot about sport as spectacle and work, which is interesting, and includes some excellent quotes involving doping team managers/DSs and barbecues.

“If testing continues to improve, in the very near future, it may no longer be worth the reward.”

Doping improves on a parallel track.

We’re into the eleventh year of cycling tackling doping with increasing rigor. What has it brought us? A decade of cycling taking down its biggest stars one by one has brought us to the point where NFL fans scoff at cycling as a doper’s paradise. Not exactly what I’d call success.

While the NFL is big business, the comparison is lacking (average NFL game has 11 minutes of actual football: https://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704281204575002852055561406.html).

Doping in ‘Merican sports involves the out-and-out use of steroids! The level of sophistication is…umm…less than in cycling.

The one lesson that cycling fans need to take from the NFL is the story of Michael Vick and dog fighting. It takes someone truly high profile to get caught (not merely admit later) to show that a problem exists and that it’s pervasive. Prior to Vick, did you really think dog fighting was a major problem, really?

While many other cycling nations have seen their stars’ collective Waterloo, America has not. We need a certain high level positive as a cathartic moment to really move forward. Paradoxically, no matter what proof is ever offered it will fall short in the minds of many. You could produce full, labeled transfusion bags, complete with DNA verification as to identity and there will still be doubters. A certain analogy concerning an American politician’s birth certificate comes to mind…

Instead of heaping criticism on cycling, these anti-doping measures need to be expanded. Let pro baseball/basketball/football deal with the kinds of out-of-competition testing to which cyclists are subjected. The problem is that with the level of scrutiny on cycling (and largely cycling alone), it does look like everyone is dirty. The only way to prove otherwise is to be beyond reproach, which requires continued and increased focus/enforcement.

Cosmo,

Timely and excellent read. I thought the same thing when I read Walsh’s comment… “oh really, going nowhere?”. Just the shear increase in outspoken riders against the doping culture is reason enough to think things are on the right track.

LastBoyScout,

Good point, re: the NFL, MLB, etc. I always bristle at the “cyclists are dopers” stereotype when it comes from fans of American professional sports. The argument that increased controls will always be out-matched by increasingly sophisticated drugs and doping programs seems like a logical fallacy to me. When we can test for compounds down to less than 1 part per trillion (most environmental sampling stops in the parts per billion), we’re starting to get somewhere where nobody can hide. Even if the drugs and the means of administering them become increasingly sophisticated, there’s no logical reason to believe they will ALWAYS be so far ahead of the testing procedures on such a scale that the entire peloton takes part in systematic cheating. Already, I don’t believe that’s the case anymore, even though it probably was 10-15 years ago.

Suppose you test for organic compounds in blood using a GC/MS. At such low levels, it doesn’t matter if you have a library match for a new drug, all you need to know is that it doesn’t belog there.

Flawed as the antidoping policies and execution may be, cycling is a long way from everybody all raging on EPO. Some Clen and one’s own blood is a lesser of two evils. That counts as progress in my book.

If anyone still has any doubts about the sport going backwards on the doping issue:

https://www.cyclingnews.com/news/wada-issues-report-on-ucis-tour-de-france-doping-controls

Maybe if BigTex is taken down (assuming the allegations are true) the message will be that NOBODY, no matter how good, famous or rich can beat the dope testing forever. Eventually you WILL get caught. If/when that happens might it no longer seem worth the risk of cheating?

The whole maternity process is not easy. Even the simple act of getting pregnant is painfully difficult for some. There are several factors which can lead to difficulty in conceiving including stress, diet, medication, infection and others. Some people choose to follow conservative but invasive treatments to address the problem of fertility. But for many, just knowing the best day to get conceive can solve the problem without spending much time and money or potentially undergoing painful medical procedures.