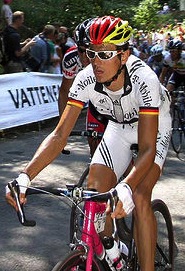

For riders not invited to the Vuelta and unlikely to fare well at Lombardy, the World Championships are now the primary concern, and, stuck with a comparatively runty team at the event, Andreas Kloeden has gone online to voice his crankiness.

For riders not invited to the Vuelta and unlikely to fare well at Lombardy, the World Championships are now the primary concern, and, stuck with a comparatively runty team at the event, Andreas Kloeden has gone online to voice his crankiness.

Kloedi encouraged his fellow riders to “stop arguing on Internet” and earn more points though the rest of the season, before going on to trash the management of the German cycling federation over Twitter; unfortunately, at last check, the UCI did not award points for irony.

In all seriousness, though, if Kloeden’s looking for someone to blame for this predicament, the mirror would be a good place to start. Dismiss the field trip to Freiburg as mere allegation and you’ll still have to explain the Lost Generation of caught and convicted countrymen and teammates that came up under his tutelage—restarting a career on some second-tier outfit is no way to rack up UCI points for your national federation.

Maybe if he and the still-delusional Ullrich had made any effort to instill some ethical foundation in up-and-coming riders, there wouldn’t be this pallid miasma hovering over the world of German cycling. Even riders who are almost certainly clean endure daily the scourge of a skeptical fanbase and reluctant sponsors—is it any wonder the most consistently successful German rider of this generation has been riding for non-German teams the entirety of his professional carrer?

Voigt himself has expressed sadness that the last German ProTour team is disbanding, but I think he’s too quick to forget the crowds on l’Alpe in ’04. Nationalism, even of the benign sort, isn’t good business practice. Cycling’s a business, and international teams and sponsorships bring the sport more money and greater exposure; I have no doubt that more reliable paychecks and happier teammates will see both Gerald Ciolek and Linus Gerdemann will perform better on foreign registered squads next season.

Voigt himself has expressed sadness that the last German ProTour team is disbanding, but I think he’s too quick to forget the crowds on l’Alpe in ’04. Nationalism, even of the benign sort, isn’t good business practice. Cycling’s a business, and international teams and sponsorships bring the sport more money and greater exposure; I have no doubt that more reliable paychecks and happier teammates will see both Gerald Ciolek and Linus Gerdemann will perform better on foreign registered squads next season.

With the continued inexorable progression of the Armstrong investigation, it might be suggested that German cycling is undergoing a dry run of what the sport in America will experience when the curtain is finally pulled back on the Bruyneel Era. But I think otherwise; along with the proliferation of top-level American teams has come an attitude, most prominently proselytized by Garmin’s Jon Vaughters that commitment to clean competition trumps results.

A welcoming environment for “the guys who said no” and a longer-term definition of success have already begun paying dividends, both for the squad—consider Dan Martin’s recent wins at Poland and the opening stage at Varesine—and for American cycling, whose Worlds team boasts a full roster, despite what was essentially a non-season for the US’ historic UCI points winner.

So when Bernhard Kohl, one of Kloeden’s former understudies at T-Mobile, insists it’s impossible to win without doping, his assessment is—perhaps in reflection of the environment he came up in—woefully shortsighted. One only need gaze upon the disasterous state of the cycling in Germany to see how much more successful Slipstream’s winless ’08 Tour was than the dope-riddled campaign waged by Kohl’s Gerolsteiner squad.